What is the true starting point of an app idea?

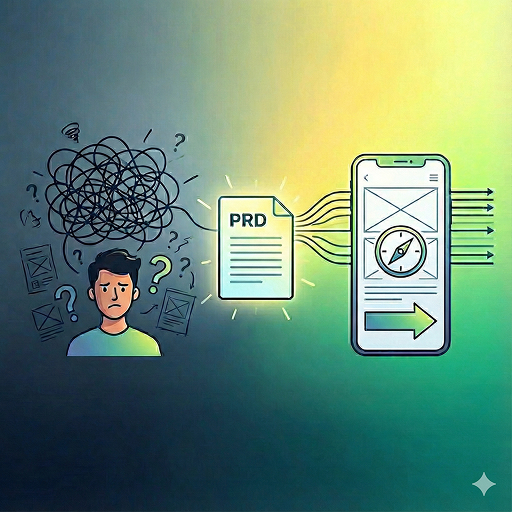

When people think of app ideas, they often start with, “It would be nice if this feature existed.” But apps that users actually choose don’t start with features—they start with discomfort. Small problems repeated in daily life, moments that feel slightly off even though they seem “solved,” or situations where existing apps don’t quite fit the user’s needs become the real seeds of ideas.

What matters here is whether the discomfort goes beyond a simple complaint and leads to a change in behavior. An app only becomes viable when users are willing to spend real time, real money, or change their habits to solve that problem.

Decision Criteria: Is this discomfort worth solving with an app?

Not every discomfort should become an app. In fact, most should be filtered out before development even begins. The criteria are simple, but if they are not clearly written into the PRD, the app starts to drift from the very beginning.

- Repetition: How often does this problem occur—daily, weekly, monthly? Problems that are “occasionally annoying” rarely become products. Repetition creates habits, and habits are what keep apps alive.

- Intensity: Is the discomfort merely an inconvenience, or is it a real necessity users cannot avoid? If the intensity is weak, the reason to open the app is weak as well.

- Substitutes: Users are already coping somehow—notes, messaging apps, spreadsheets, existing services, or simplytolerating the problem. The question is whether your solution can be clearly better than these alternatives.

- Behavior Change: Does solving this problem actually change user behavior? The key is not “this sounds nice,” but “this makes people act differently.”

- Market Context: Are there already apps solving a similar problem? If so, that’s not the end—it’s the beginning. You must identify what those apps fail to solve.

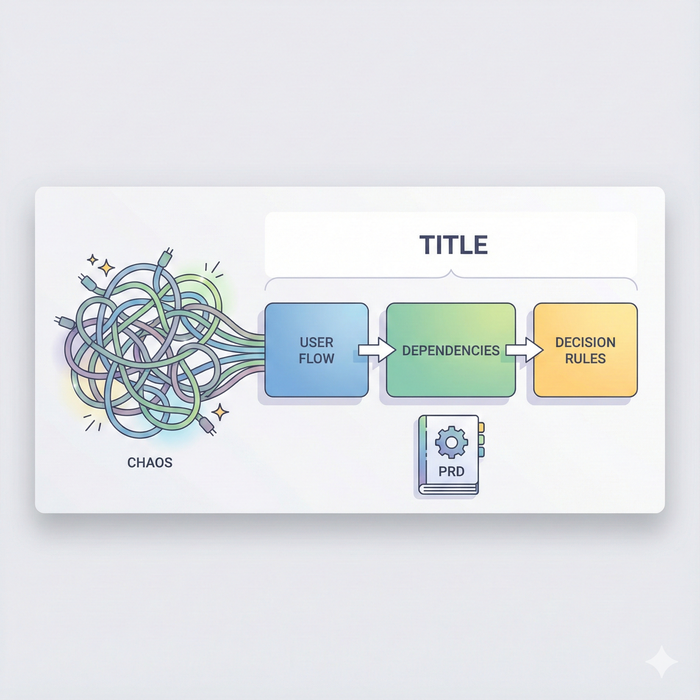

These judgments can be discussed verbally during ideation, but they always fade over time. That’s why a PRD is necessary. The PRD fixes the discomfort in place and translates it into the language of a product.

Comparison: What’s the difference between apps that start from discomfort vs. features?

Apps that start from features move fast at first. Listing features immediately creates tasks to work on. But over time, as features accumulate, the core disappears. The question “Why did we add this feature?” keeps resurfacing, new assumptions pile up, and the app gradually loses direction.

Apps that start from discomfort may feel slower at first, because the problem must be defined precisely. But once that definition is clear, decision-making becomes much easier. Every feature is judged by a single set of questions:

- “Does this feature directly help solve the discomfort?”

- “Will users actually use this at the moment they experience the problem?”

If the answer is no, the feature is naturally excluded. As a result, discomfort-driven apps often have fewer features but stronger usefulness, while feature-driven apps tend to have many features with weaker meaning.

Outcome: PRD is the tool that turns discomfort into direction and scope

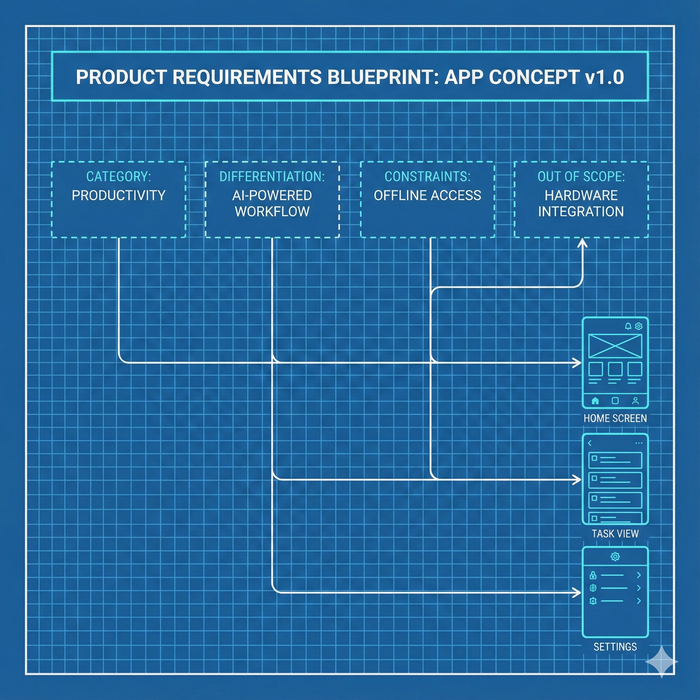

Here, the PRD is not just a template—it is a shift in thinking. To turn discomfort into a product, the PRD must clearly define the following:

- Problem Statement: Fix the user’s discomfort into a single sentence. If this sentence wavers, the entire app wavers.

- User and Context: Specify who experiences the discomfort, when, and where. The same problem in a different context leads to a very different app.

- Approach: Instead of jumping straight to a feature list, define how the problem will be solved. Whether the solution focuses on fast input, automation, or recommendations completely changes the product.

- Scope: Separate what will be built now from what will come later. A PRD without scope constantly pulls in more features.

- Differentiation (Against the Market): If similar apps already exist, the PRD must clearly state—even in one line—how this product will be different. Differentiation should be fixed as direction at the start, not debated right before launch.

- Validation: Define the minimum way to verify that the discomfort is real and the solution works. Interviews, a simple MVP, test messaging—some form of validation is required to turn a “good-sounding idea” into a viable product.

In short, the PRD translates discomfort into a form the team can actually build. The more accurate this translation is, the less development wobbles—and the less features wander without purpose.

Summary

Most apps appear to start from features, but in reality they begin with a single uncomfortable moment. What matters is whether that discomfort is repetitive, intense, and solvable in a way that is clearly better than existing alternatives. By fixing this judgment into a PRD, the idea transforms into clear product direction and scope.

When problem statements, context, approach, scope, differentiation, and validation are defined in the PRD, an app stops being just an idea and becomes an executable product.